It would have been sometime around 1979 or 1980. I left from my house on Darley, so buying that house (my first) marks the early limit, and construction on the dam, which was definitely not going on when I ran, marked the latest limit. Work on the dam started in earnest in the fall of 1980, with construction of the river diversion. I think I can figure this out, someday.

El Rio de Nuestra Señora de Dolores, River of Our Lady of Sorrows. The greatest sorrow for the river, and a great sorrow for me, was coming. I knew I needed to run this river before they built the dam. I needed to run it through the “take area” and, while I am at it, I should run it to its mouth. I knew I didn’t have much time. No one else wanted to go just now.

And now, the end is near,

I’ll do it my way.

That was, without a car.

I caught a ride to the FibArk slalom race with my housemate Linda Hibbard. I raced, though I have no recollection of how it went. This may have been the year I paddled almost solely C-1 (for a new challenge). If so, then I finished third (as I recall), which was probably also last. There were not a lot of C-1 paddlers in CO.

After the race I caught a ride to Durango with another racer. Can’t recall who, but it was one of those guys who beat me regularly. That is, a good slalom racer. I hauled my touring boat and paddle, and all my gear (pretty lean); Linda took my racing boat and paddle back to Boulder.

I remember that I stayed with Pres Ellsworth, a river outfitter, in Durango. I met Pres through opposition to the Dolores project, and probably also opposing the Animas La Plata Project. I probably would have gotten together with the ALP women, led by Jeannie Englert, but I think that by then Jeannie and Tim might have moved to Lafayette. Both efforts at opposition were futile but worthwhile.

So far, so good, but the really good stuff was about to begin. The next morning, Pres dropped me off on CO160 on the west edge of Durango. I stood there with my huge Lowe Expedition pack, kayak and paddle for…not very long. Amazingly, I had only been standing there a short time when an orange-ish VW van with a family going to Mesa Verde stopped and picked me up. Recently, I think I found a vestige of that ride–a note or something that I connected by inference–with a name. (Maybe somewhere there is a journal, but I was not good at that. And, I didn’t take a camera–maybe the Olympus XA had not yet come into my life as a camera I could carry in a ziplock bag.) Maybe someday I will figure this out, too.

The family in the orange-ish van dropped me off at the exit to Mesa Verde. It was an exit–two-lane 160 expanded into four lanes for a short time, so rather than battle across oncoming traffic from a left turn lane, you could exit and go under the highway–very deluxe, and probably the same structure that is there now, but embedded in miles and miles of four-lane roadway.

I’m still not sure what prompted me to do it, probably that traffic was sparse, this being a Monday (Slalom races ran on Sunday; course setting and practice was on Saturday), but I ran (sort of) up the ramp, toting my boat on my shoulder and my pack on my back. I didn’t want to miss a car, even though the odds were low that anyone would pick me up. My idealized memory is that the first car stopped, and that fits into the serendipity of this trip, but that’s probably too good to be true. In any case, I did not wait long until a young fellow stopped. A teenager, high school age as I recall. He lived in Dolores! That’s my put-in.

My plan only went that far–I did not know for sure where or when I’d sleep. I probably had Plan A, Plan B and Plan C. A being an afternoon launch and camping down the river a ways. B would have been staying in or around Dolores, and C would have been back on 160 somewhere.

The Kid worked at the Pizza Hut in Cortez, and he was going to work. He told me he would take me down to Dolores after he got off work, sometime in the evening. So, Plan B it was. I remember going to a movie and then going to the Pizza Hut to eat, and to leave a tip. l probably left my boat and gear on The Kid’s car. God, do I wish I’d had a camera to boost my recall. That evening, The Kid dropped me at the park in Dolores with assurances that the sheriff would not roust me. The next morning I ate across the street and set off. It was roughly 200 miles to the confluence with the Colorado, only a little shorter distance than the usual run through the Grand Canyon.

I had little gear–probably no tent, just a tarp, a very light, compact down sleeping bag, stove, one pan and a water bottle. Filip and I pared down gear when we ran the Chixoy-Rio Negro-Salinas-Uscumacinta a couple of years before. It all fit into three or four large heavy plastic bags, which in turn fit into light, ripstop nylon bags (enormous stuff sacks, I had made). The Lowe pack went behind the seat. All the bags would fit into the pack, so a portage involved jumping out of the boat, pulling the pack, stuffing the bags into the pack, shouldering that and the boat and tottering off, using the paddle for balance. I didn’t plan to portage anything on this trip, but Filip and I had finely choreographed the portage in Guatemala.

There were several landmarks on this trip. The first was Bradfield Ranch, the usual put-in to run the Upper Dolores. Next was Snaggletooth Rapid. There were more, but this day all that counted was Bradfield Ranch and Snaggletooth. I had no idea how many river miles it was to either. Nobody ran this upper-upper stretch, and there were no maps.

Probably there was a map–somewhere the Bureau of Reclamation had a mile-by-mile map of the river that showed all the dam sites. I didn’t have this, though. The only map I had was a Xerox from a EIS on something like oil development, which showed the lower river, from somewhere near Snaggletooth to Bedrock, where it enters the Paradox Valley. That is, it covered the Slickrock to Bedrock run, AKA the Lower Dolores. I was running past there, to the Lower-lower Dolores, and on to the Lower-lower-lower Dolores and to its confluence with the Colorado River, just above the departed and much-missed Dewey Bridge.

I knew from reports that I could run the river all the way from Bradfield to the confluence, but there was Snaggletooth. The rapid was described with respect–Ron Mason had once carried it when he ran the Dolores in a wildwater boat–but by now I had been kayaking seriously for five years or so and I’d run the Grand Canyon two or three times and much class IV and even V water. I was not concerned. Mason was a ninja, but he was in a long and tippy wildwater boat.

Snaggletooth was no factor the first day. As I am wont to do I probably lingered over breakfast and coffee, getting a late start, and the river mileage was longer and the gradient lower than my idealized notion. I stopped somewhere above Bradfield Ranch, I really didn’t know where. The next morning, I got an earlier start and set off. Perhaps I stopped at Bradfield–I don’t recall–but my mission was to get to Snaggletooth. That that was my mission does reveal that I was at least paying respect to the rapid. I was really probably anxious about it, as it was an unknown, and Mason had walked.

I said to myself that I would stop and pee when I got to Snaggletooth. Maybe I was planning to get out to scout it, rather than scout it from the boat, or maybe this was an excuse to allow me to get out without admitting any weakness. Anyway, I stayed in the boat and paddled onward below Bradfield. And I paddled and paddled and paddled. I’d run a number of sharp but not stressful rapids, and I’d gone what felt like a long way. I should have been to Snaggletooth by now, and I really had to pee. I convinced myself that Mason had had a weak day and that I had passed the rapid, and I got out and peed. But, it’s easy to overestimate how far you’ve traveled on a river in a narrow canyon, and I am an optimist.

Snaggletooth, in its reality, is no-shit rapid. It’s equal to rapids on the Selway. That’s the first impression I had when I came around a sharp corner and heard the roar. There is no option to scout from the boat, at least at the water level that day–there is a horizon line, and big splashes come above it from a surging hole below. That’s the style of approach you have to big rapids on the Grand Canyon.

Scouting big rapids leads to two states–tranquility or bowel-loosening vigilance. There are three ways to get to those two states. Category 1: At your first glance you see that the rapid is easy. Category 3: At first glance you see that it is clearly unrunnable. Like most things in life, it is the middle, uncertain situation where the hard decisions must be made. Snaggletooth fell into Category 2: clearly runnable, but demanding a near-perfect run. That day, for me, then, it fell into Category 2. Now, for me, very likely, almost certainly, yes definitely, it would fall into Category 3.

The run was not notable. At least, I don’t have any recollection of it, so I infer it was not notable. No missed strokes or miscalculations. No rogue waves, flipping me over or surfing me to the hole formed by the snaggletooth rock. I’m sure I was exhilarated. Jubilant. Relaxed. More odd serendipity was around the corner.

Not far below Snaggletooth, the Ponderosa Pines appear at river level, and the Dolores begins to embed itself into the massive Wingate sandstone. Quite suddenly it feels like a desert river. It’s no coincidence that the next road crossing is at the town of Slickrock.

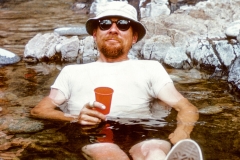

Very near Snaggletooth–memory fails, but the circumstances dictate “very near”–I was paddling lazily along, probably looking for a place to eat lunch. I was along the right shore when I saw something bright on the river bottom. The Upper Dolores watershed is reasonably mature, so the upper river is clear–its gradient and water are somewhat reminiscent of the Middle Fork of the Salmon. Not crystal clear, but pretty darn good. That would change downstream, but right now, on the receding limb of the hydrograph, I could see the bottom, and there was something odd there. I paddled over and reached down, still in my boat, bracing myself with the paddle. Aluminum. More brushing, more aluminum. Digging. More aluminum. I got out of the boat and dug more. A big, flat surface. A rounded edge. It became apparent as a very large commercial saute pan. I found a handle and pulled it out. That stirred up a lot of mud, but not so much that I could not see another, nested pan. Pulling that one out revealed another, and then another. Four in all. Some commercial rig had flipped in Snaggletooth on the high water, and here was where the inadequately stowed frying pans finally fell off the inverted raft.

Damn do I wish I had a selfie of me and those crazy frying pans. But, I still have three.

One of the central problems of my personality is the feeling, about just about anything, that “this might come in handy some day”. I’m sure this is a residual of parents who lived through the Great Depression. When we cleaned out their house after Mom died, we found a drawer half full of rinsed, dried and neatly smoothed and stacked plastic bags. The frying pans were clearly going to be mine, but the question was, how? By now I was within the domain of my Xeroxed map. I could see that a side gulch a few miles down led, with a climb of a couple thousand feet, to a place on the rim where an old uranium road came near. So, I sat the pans on my lap and paddled on. The road was there, just as my map said, and I stuffed the pans into a rock cavity and covered them up. I took a good look at the details and walked back to my boat. I would be back, but it would be years.

Where I went next I don’t recall. Downstream, of course, but how far escapes me. I probably passed Slickrock and camped. Slickrock is the normal put-in for the Lower Dolores–its the first bridge below Bradfield–but no one was there that day. I doubt I worried much, because I would be returning from the Dewey Bridge on Utah 128, along the Colorado River, and the usual river runners would offer no logistical advantage. In fact, it might have been a bad thing to run into another trip there, because they would very likely have been getting out at Bedrock, and I would have been tempted to join them. (I might have been able to snag a beer or two, though. Beer was not in my spare commissary.)

The next place I remember is just inside the entrance to the Dolores Canyon on the downstream side of the Paradox Valley. It’s a paradox because the Dolores flows across the valley, cutting into the valley through one wall and out of the valley right through another. These are Wingate walls–cliffs–so the entrance and exit are spectacular. The river was probably once superimposed on a rising dome, in a continuous set of meanders, but then the underlying salt collapsed forming the valley, and the river stayed on its course. There was no other way to go–either end of the valley is up hill. The river’s exit from the valley is dramatic, and it promised nicer camping than in the cow-pulverized, shit-strewn, unsheltered valley bottom. Shortly after I turned the corner I hunkered down below a cliff and out of sight of the road that ran along the river. Serendipity was about to strike again.

The Y11 road above my camp ran from CO 90, just east of Bedrock, across the floor of the Paradox Valley, and along the Dolores to the mouth of the San Miguel River. Y11 had been used to haul uranium ore from mines on the exposed strata of the north rim of the Paradox Valley, thence up the San Miguel to Uravan, where there was a notoriously dirty mill. Uravan is now just a site, with just a couple of buildings standing. They may be off limits. At the time I passed through, the mill at Uravan was running, as it had since the early parts of the 20th century. It began refining radium ores, and then switched to uranium ores in support of the Manhattan Project, and during the cold war. It was a sloppy, grown-like-topsy operation, and much radioactive contamination escaped and was left. Eventually, it was cleaned up, as much as is possible, through the Superfund program. In the oughts I worked as an expert witness on litigation between residents of the company town and Union Carbide. Gerry Spence was the plaintiffs’ attorney.

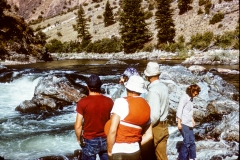

After the Y11 road turned up the San Miguel, the Dolores Canyon looked untouched for a bit, but in a short distance the remains of the Hanging Flume came into view. I’d forgotten about this, so it was a bit of a shock. The flume carried water from high up the San Miguel and then along the Dolores to alluvial deposits of silver, preserving enough head to allow for hydraulic mining. It’s a crazy thing–it clings to the sheer Wingate walls. Now it has been restored in reaches, but then much of the remains were fragmentary. A little bit further CO 141 comes into view. I’d crossed under 141 at SlickRock–It begins in Dove Creek and then takes a big, S-shaped route, first eastward, then back westward to the Dolores, following it to Gateway. When the Dolores turns west and cuts its way between Steamboat Mesa and Polar Mesa to the Colorado, highway 141 heads northeast, up Unaweep Canyon to Whitewater, along Highway 50, just south of Grand Junction. A geologic instant from now Unaweep Canyon will capture the Gunnison, confounding Colorado Water rights holders.

The Dolores Canyon along 141, from the San Miguel to Gateway is national-park spectacular. Like UT 128, there are parts of the road that rival Zion. The road is an unwanted intrusion onto the river, but in those days it had little traffic, so you could mostly ignore it.

Sometime that day, below the San Miguel, I came around a corner and saw a couple of rafts. They were small below the vast Wingate cliffs, but they were very interesting to me. No one ran this stretch–what were they doing there? As we approached there was a moment of puzzled half-recognition. Did I know this guy; he was asking himself the same question. In a moment, replacing the context, I recognized Tom Bryant, a young hotshot kayaker from Boulder. We had paddled together only a couple of times, but kayaking in those days created tribal bonds.

Tom, it turns out, had organized this raft trip for a bunch of friends to run this lower-lower canyon of the Dolores precisely because it is seldom visited . Wonder of wonders, lightning strike of serendipity, they were going on to run the lower-lower-lower canyon from Gateway to Dewey Bridge. Here was my ride home. To my front door in Boulder, as it turned out.